Every nTLD has its own unique geography, if only because of language. The Spanish .VIAJES is viable throughout Latin America, whereas .IMMOBILIEN is only at home in German-speaking Europe. .TIENDA tends to be registered more often in Spanish-speaking nations, as does .FUTBOL. And it would certainly be strange if .شبكة weren’t mainly concentrated in the Middle East.

When a TLD + Country occur together at an unusually high rate, we’d say the TLD skews toward that country (or vice versa). Please refer to this table of Skew data. Here’s my definition:

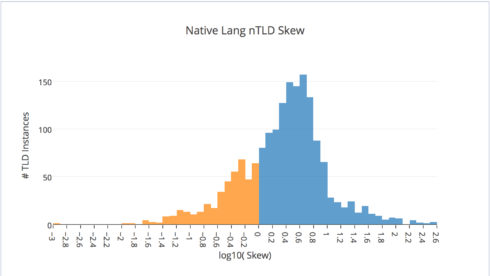

In the previous article, we measured Skew for GEO nTLDs – suffixes like .LONDON, .BRUSSELS, and .WALES, which are defined by locality. Language can cause skew also, but this effect varies. Vietnamese is spoken mainly in 1 country. German in 3. Spanish is more widespread. And English, meanwhile, is very nearly ubiquitous. Therefore we’d expect English to skew less than languages that are more regionally limited.

Don’t be intimidated by the logarithmic axis. You can read the Skew values by referring to this key:

| Skew | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 10 | 100 | 1000 |

| Log10(Skew) | -3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

What you see pictured above is straightforward: We’re counting how many nTLD / Country pairs stick together more than usual. When Skew = 100, that means the couple holds hands at 100 times the global rate. This appears as Log10(Skew) = 2.0 because 102 = 100. If that sounds confusing, skip it. The following facts are all you need to know:

- The blue region shows cases with positive bias.

- A tall peak means many TLD / Country pairs have this value of Skew.

- The bigger the number on the right, the more intense the bias.

We’re excluding GEOs, which have Skew as high as 1000+. Among non-GEOs, it’s rare to see Skew as high as 100. When there is Skew at all, it’s generally less than 10 – which is why most of the blue region falls between Log10(Skew) = 0 and 1.0.

Compare the histogram above with the one below. Look how much higher the blue peak is for native language nTLDs. It’s no surprise: Registrants naturally gravitate toward suffixes in their native language and shy away from suffixes in foreign languages.

We’ll see something much more striking if we divide English nTLDs from non-English:

Again, most of the blue region falls between Log10(Skew) = 0 and 1.0. This means English suffixes are rarely registered by any country at a rate more than 10 times the global average. Usually, when there is Skew at all, it’s somewhere between Skew = 1.0 (i.e. no bias) and Skew = 10.

Yes, there are cases where an English nTLD is highly overrepresented in some country such as the Cayman Islands / .PROPERTY (Skew = 277.1) and Ireland / .ORGANIC (Skew = 113.8.) But the vast majority are more like India / .EDUCATION (Skew = 2.8) and New Zealand / .FISHING (Skew = 2.8). Both are registered at a rate 2.8 higher than the global norm, yet that’s nowhere near the Skew ≈ 1000 of local GEOs such as Ireland / .IRISH or South Africa / .CAPETOWN.

As lingua franca, English is indeed so universal that it doesn’t even need to be a native language to have high Skew. For example, consider Norway / .GOLF (Skew = 96.3), Greece / .VILLAS (Skew = 75.7), or the Czech Republic / .CLOUD (Skew = 72.0).

Now look what happens with non-English suffixes! Other languages are well represented in the nTLD program – French, Spanish, German, Chinese, Russian, etc. It’s not that “foreign” nTLDs are unsuccessful. However, it’s abundantly clear that registrations in non-English suffixes are FAR more locally skewed. In fact, non-English nTLDs will be found overrepresented by a factor of 10.0 to 353.6 more than half the time.

Conclusion: English nTLDs are registered more uniformly all across the world.

This latest Domain News has been posted from here: Source Link